Investigative journalist and author Justin Mikulka joins me to discuss the recent train derailment in East Palestine, bomb trains, and the devastating consequences the lack of regulation of the railroad industry is having on the environment and human communities across North America.

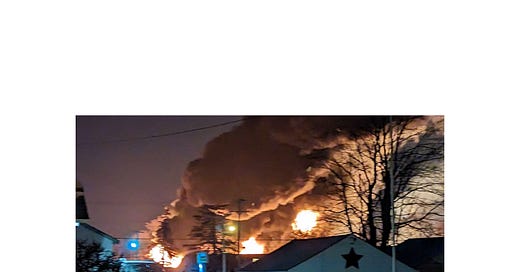

On February 3, a freight train operated by Norfolk Southern derailed in the small town of East Palestine, Ohio. Train derailments in North America, and particularly in the United States, are shockingly common, due to a variety of factors discussed in this interview. What makes this derailment of particular concern, is that it resulted in the voluminous spilling and burning of toxic chemicals at the site, the plume of which could be seen from space. Of the chemicals spilled, vinyl chloride has been the one given the largest attention and concern.

In an article written by John McCracken for Grist, vinyl chloride is described as “a colorless gas that is linked to various cancers and is used in a variety of plastic products and manufacturing. In the initial days after the derailment, temperatures rose in the cars holding the vinyl chloride and officials at both the railroad company and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, ordered that residents evacuate East Palestine.”

A few days after the release of toxic chemicals at the site of the crash, Ohio Governor DeWine remarked “that prior to the decision to release the chemicals, he was presented with ‘two bad options.’ One was to do nothing and risk that a train car full of vinyl chloride would explode, which would have been ‘catastrophic,’ resulting in shrapnel flying out in a one-mile radius. The second option won, and officials conducted a controlled burn of the chemicals.” Numerous other deeply concerning chemicals were leaked in the derailment site and burned. As reported by Jill Neimark for Stat News, those substances include: butyl acrylate, ethylene glycol, isobutylene, ethylhexyl acrylate, benzene, petroleum lubricating oil, and more. Truly a deadly, cancerous cocktail for all the reasons you can and should expect. This is an environmental catastrophe, definitely one of the worst to occur in recent decades. Residents of East Palestine and surrounding areas are reporting numerous health issues, with high levels of toxins in waterways, on the ground and in the soil. There are reports of thousands of dead fish, sickly wildlife and pets, and numerous other troubling things.

This is not an anomaly. As I mentioned previous, train derailments are shockingly common in North America. Why is that? Why has nothing changed, and why, to use the words of Mikulka, will this happen again?

This interview was recorded Feb 25, 2023, and released as episode 340 of Last Born In The Wilderness. The transcript that follows was edited mostly for clarity, and somewhat for length.

FARNSWORTH

Because of what happened in East Palestine, Ohio, more and more people in the United States are becoming acutely aware of the dangers that exist around the railroad industry. My first question is: How did you get into this? What were the precipitating events or concerns that led you down this path of becoming one of the [foremost] journalists covering this subject so closely?

MIKULKA

It was an accident. In 2013, I was living in Albany, New York, and had been there about 10 years and pretty involved in local politics in the community. So, I knew what was going on in the city and what issues we faced. Albany is right on the Hudson River and has a large working port, although it's separated from the city—if you're in Albany, you don't even know the port is there.

In late 2012 there was an article in the newspaper that said an oil tanker had run aground in the Hudson River a couple of miles from Albany— thankfully, oil tankers now have double hulls. The outer hull was pierced, but the inner remained intact. We didn't have a major oil spill on the Hudson River, which would have been disastrous. Those of us who care about these sorts of things were somewhat surprised. The main questions were: Why is oil moving from Albany down the river, and where's the oil coming from? We learned Albany had become the largest oil distribution hub on the East Coast, bringing oil from North Dakota in by train and some of it stopping in Albany, being unloaded and put on ships—I believe that one was headed for a refinery on the east coast of Canada. But other trains then would continue down along the Hudson River, and so our initial concerns were we narrowly avoided a catastrophic oil spill in the Hudson River, and then learned these trains were running on the rails right along the river.

Something I learned after that is railroads very often follow waterways due to the favorable topography. In the East Palestine [derailment], the contaminants went into the river, and in the majority of the oil train accidents, oil ends up in a river. It's another additional environmental risk of the rail industry when it comes to these things. So, we had concerns about that.

Then, in July 2013, one of the Bakken oil trains from North Dakota bringing oil to that same East Coast refinery in Canada, derailed in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec. It exploded and killed 47 people, and basically wiped out the whole downtown. Right after learning of that, Albany and other people around the country were learning these are the same trains that are coming through our city. [We asked], “So, what's going on here?" There was a lot of confusion after that initial accident, because people from the oil industry were saying crude oil doesn't explode like that, and something else must have happened.

Subsequently, what we learned was the oil that comes out of the ground in North Dakota is very light. It includes things called natural gas liquids. It's not just crude oil, it has butane and propane in it, and that's what caused that and many subsequent explosions. It led to these trains being called "bomb trains,” with the origin of the name attributed to the men and women operating the trains. As you can imagine, if you were driving one of these trains, and then learned what was happening—the oil workers knew that they were at risk, and that these trains were dangerous.

Learning all that, it seemed like a huge risk. [Something like] two trains a day were coming into Albany, right through the city and parked next to schools and public housing. I made a short documentary, a five or six-minute film, about the risks and what we knew at the time, and got some attention. The people at DeSmog asked to run it on their site, and then to write an article. I always liked to write, and so I wrote an article.

Five years, a hundred articles, and a book later, I basically had finished covering the topic. Thankfully, there hasn't been much work to do on this issue for the last few years. The amount of oil being moved by rail has dropped dramatically, for various reasons, and the risk has been greatly reduced. But as we're learning now, there are many things moving by rail that can cause real environmental disasters and threats to the human population living along the rails.

FARNSWORTH

Yes, it seems like regardless of whether they're transporting crude oil or chemicals via rail, we don't even know what's passing through cities and towns across the United States and North America. We don't know what's on these rail lines. We assume, obviously, various goods are being transported, but the hazardous or explosive nature of them is not really well known. There is still an assumption an agency like the EPA, some regulatory body, is keeping tabs on this. If we're to take Governor DeWine seriously on what he says, that he did not know in East Palestine there was a freight carrying hazardous chemicals and wasn't actually labeled as such, it means many people, including politicians and political leaders, are in the dark about what's actually being transported through their states or districts. How did we get to a situation like this? What kind of deregulation, or other processes, have occurred over the past several years or decades that led to a situation where this could happen?

MIKULKA

It goes back to the whole history of the rail industry. The railroads have always been very powerful. Prior to the rise of the oil industry, they were the most powerful industrial lobbyist group, and had the most sway over regulations and laws. The railroads have always been unsafe. There's a good book called Death Rode the Rails that covers, from the 1850s to 1960, the different ways the railroads essentially have disdain for the public. They say, "We're the railroads, we keep the economy running. Just let us do our jobs." And whenever anyone questions what they do, they'll either say, "We can't give you that information, because it's a security risk," or, "If we share what type of products we’re moving, our competitors will know what we're doing." So, they always have reasons why they won't share the information and won't tell.

In the case of DeWine, I wouldn't expect the governor to know what was moving through. I think in this case, he actually has a decent argument. Most politicians aren't getting that information. The railroads, if they share it with anyone, share it with first responders. But it was very difficult when when the oil train issue was happening. Communities were asking, "We deserve to know how many of these trains are coming through. When are they coming through? How much? Where's it coming from?" The rail industry's initial response was, "That's classified national security information. We can't tell you." And when people dug into that, it turned out, when you asked the National Security Agency [NSA] who supposedly had said that, they responded by saying they said no such thing. The railroads are just lying about it. And you can see it play out with Norfolk Southern in this situation. Initially, they give wrong information, or they don't give the information. Then, they say everything's fine. And so we're progressing; they continue to concede a little bit along the way.

It's always been a situation that the railroads have a very powerful lobby. They very effectively, especially with the Trump administration's help, fight any regulation and worked to deregulate. Much of it comes down to a very simple thing: safety cost money, and they don't want to pay for it. If no one will make them pay for it, they're sure not going to volunteer. Norfolk Southern made $4.6 or $4.8 billion last year, they can afford to pay for it. They just choose not to. And unfortunately, our regulatory system and politicians are the only ones who could force them, and they haven't done that.

FARNSWORTH

If I remember correctly, after this incident in East Palestine, a Norfolk freight derailed in Michigan. It didn't explode. [Prior to the East Palestine disaster, a Norfolk Southern freight derailed in Ohio, spilling paraffin wax.] There are so many of these chemicals being transported for various manufacturing purposes. It's quite disturbing, [considering] trains derailing and malfunctioning is not an anomaly. It's not a little blip in the system, and seems to happen quite often. Could you paint a picture of just how frequently trains derail?

MIKULKA

I don't have the latest numbers. I've seen various ones in the articles people are writing now. But yes, it's very common. Thankfully, if a coal train derails, it spills a bunch of coal, and they have to bring in front end loaders and move the coal, there aren't environmental impacts or the threats to the public that happens when trains are carrying hazardous and flammable materials. But, it's pretty common. Just in the past couple of months, I've seen examples of trains hitting trucks because they don't always have the proper gates that come down on the crossing. So, this is not a rare thing. It's just a cost of doing business for the railroad.

There are many ways we could reduce the number of derailments, and the severity of what happens in a derailment. I don't know whether you've seen the aerial photos of the derailment [in East Palestine], but it's classic—they just go up into like an accordion. The physics of what's going on, and why these brakes used on these trains are inadequate and need to be replaced, is based on air as opposed to electronic modern ones—it's an air pressure system. The air pressure has to travel the length of the train to brake, and so front cars start to brake first. When you start slowing down the front of the train, those back cars are still moving before they start to brake. That's why you get that accordion thing. The train is essentially running into itself. The railroad will say they have another locomotive at the end or in the middle that is also braking to try to address that. There's a ton of research—it's all in the articles I've done, and I've got a chapter in my book on it.

One of the advantages of modern brakes is it’s instantaneous—an electric signal. Every car starts braking at the same time. It greatly reduces the forces involved in the derailments, but also the amount of cars that leave the tracks. And, it decreases the severity, if not avoiding or preventing some of these accidents.

FARNSWORTH

How old is this air braking system?

MIKULKA

It's commonly referred to as Civil War technology. In the 1850s or 1860s, I think, a couple people came up with different designs, but they're air brakes—based on air pressure. And yes, it's ancient, and should be replaced, and it was.

When I wrote about and followed the regulatory process after Lac-Mégantic and other oil trains were derailing and exploding, people said we need some new regulations. They looked at tank cars—they really should have stabilized the oil to remove natural gas liquids, so they wouldn't explode and act like normal crude oil. There are many different things they looked at, but the oil and rail industry have effectively fought pretty much everything, except the braking mandate. They were given eight years to phase that in, but then effectively repealed that as well. It's unfortunate. We know, and the industry knows. You can see the comments coming from the lead lobbyist or spokesperson for the Association of American railroads, saying these brakes don't work, and they're not safer—I don't think she even says they're too expensive. This directly contradicts many of the things the Association of American railroad said ten years ago, when they were touting these brakes as a great new safety advantage. The one area where they specifically went on record for that was when they wanted to move radioactive waste—spent nuclear waste—by rail, which is something that happens. They said, "To assure people that it would be safer, we're going to put these modern brakes on these—they're much safer, so we're going to put them on." And so they know, they admitted it on record.

There's no other way to say it: they're lying about it because they don't want to pay for it. I believe this spokesperson argued that the brakes failed and the train is stuck in place, they would have to shut down the rail system. Both Australia and South Africa run modern rail systems. Australia's pretty large country, and they use these modern brakes. What they have found is they actually save money.

FARNSWORTH

I don't know what the costs are to clean up, or at least remove and move these derailed cars, and fix up the rail line again. I don't know what the cumulative costs of even doing the bare minimum to get these rail lines up and functioning again, in comparison to the long term goal of making these more safe. Even though I recognize the short term profit motive thinking that's involved in this, I still have a hard time making sense of why they don't invest in really good infrastructure, brakes, and safety mechanisms that will, for all the obvious good reasons, protect the public and the environment. That should be the highest ideal, but it's not. Even in the most cynical way of thinking about it, why don't railroad companies invest in some of the most basic things? Yes, it's going to be a bit of a cost at the beginning. But over time, they're not going to be having as many of these accidents, spilling all of their product into the ground and having to come clean it up, if at all.

MIKULKA

You're thinking like someone who's trying to build a long term business as opposed to getting a quarterly bonus. Unfortunately, this is really all driven by Wall Street.

A good example of that is something called positive train control. Basically, positive train control is having a computer managing and overseeing the train's operations. There was a derailment of an Amtrak train around Philadelphia a few years ago. An engineer was operating it, but went into a corner at 110 or 106 miles per hour, but should have been going 60 miles per hour. I've never heard a good explanation why that happened, but it was human operator error. If you had positive train control, there would have been alarms going off, saying you're coming in far too hot for this corner, and would automatically brake the train.

This technology was first recommended by the National Transportation Safety Board in 1970. The rail industry refused, all the way until 2008. Then, in 2008, the Congress passed the Rail Safety Act and said they have seven years to do this. "We've been asking since 1970. In 2015, everyone's going to have to do this. We're giving you seven years." So, fast-forward to 2015: the rail industry hadn't done it. I sat through several congressional hearings where people in Congress were saying it doesn't appear they're going to make the deadline. And [the railroad industry] responded, "Yes, we're not." No one seemed to say that's unacceptable.

I was very naive going into this whole process about how regulation and Congress works. And then, when they did start to get pressure, they basically said, "Fine, we're not going to on your timeline. We'll stop running our trains and shut down the US economy." And on the AAR [Association of American Railroads] website, there was an image of a nice, bright economy on the left: "Here's America in the light. And here it goes to the dark when we stopped running the trains." So, they essentially held the economy hostage.

It took them another six years, I believe, to finally implement positive train control—50 years after they were supposed to. Along the way, a lobbyist for the Association of American Railroads was given an award by the lobbying industry at an annual conference where people get awards for top accomplishments, specifically for the fact that they had delayed the safety regulation. There was another reporter that found on an earnings call for one of these railroads the analysts—the Wall Street people—saying, "You got to delay this, we're not spending this money." Wall Street is pressuring them, saying they want to make quarterly profits, and this doesn't help. It's that simple. Will this help profits? No, then don't do it. That's the attitude.

So, this guy accepted an award for delaying something that, I think when the Amtrak train crash, killed eight people. They were saying at least 250 lives could have been saved if positive train control had been implemented. It’s an attitude very emblematic of the rail industry towards safety versus profit.

FARNSWORTH

In East Palestine, when people were evacuated from the town after this derailment, it was then declared safe that they could go back home. And as I mentioned, there are reports of people’s pets dying, chickens dying, and finding dead fish in the creek. They're experiencing numerous physical side effects, and are very worried about drinking the water. So, they're told by a regulatory agency, the EPA, that it is fine to go home, and the water is safe. Obviously, it's not. I'm sure there's plenty of independent testing that's being done to verify the recognition the residents have.

Regarding the role of these regulatory agencies, their role is to "regulate" the railroad industry, but it seems they're just partners [with the industry] and giving the rubber stamp of approval. ”What you're doing is very dangerous and unsafe—technically, you shouldn't be doing what you're doing. But, we're giving a stamp of approval. You can continue doing it for the enormous amount of quarterly profits you're making on this." As you mentioned, you came to these hearings, looking at how they're trying to regulate the industry, and had a naive assumption of how this was supposed to work, which is something I think many people would feel when they first enter into one of those things. What was revealed to you about how the regulatory agencies actually operate and how they work with the railroad industry?

MIKULKA

That's the thing that was most surprising to me. I had some experience in corporate America in my background, so I understand how some of these things work. But I was shocked by how when the regulatory process started and asked how to make trains safer, in the public meetings we were allowed to attend, every time, in every meeting, individuals from the American Petroleum Institute and the Association of American Railroads were seated right at the table and often leading the discussion about how we would make these new regulations. So, recall that I just said one of these lobbyists got an award for delaying safety regulations, and yet they're the ones at the table with their lawyers saying “it's unacceptable.”

When the regulations were being made for oil trains, which were more broadly for high hazard trains, the oil and rail industry got together and wrote a letter to the Department of Transportation. The Department of Transportation includes the Federal Railroad Administration [FRA], which then also includes the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration [PHIMSA]. PHIMSA is the actual group that makes these regulations. They got a letter from both industries saying, "We're willing to work with you on this, but there are two things we're not willing to accept: speed limits and making us stabilize the oil before we put it in these trains." I argued for years stabilizing oil was the only sensible thing to do, because when you have an environmental disaster like an oil spill, it won't burn down a town and kill 47 people. But that's what they did, and that's what they got. They set the rules of: "We'll negotiate about some things. But, there's certain things that we're not going to accept being regulated." That's the power that they have.

I just figured regulations were based on science, but it's not, and that's where I was very naive. And then, actually, the science is perverted. These lobbyists say electronic modern brakes don't work. They're just lying, but they can always come up with a study. A study that you paid for! It's never an independent peer reviewed study. So, it's a huge thing we're up against. A phrase that they use constantly is, "The science is still out on this issue." It's something they used with climate change. "We're not sure why these trains are exploding, we need to study it some more." That's the level of absurdity that we're dealing with, where the oil industry was saying they don't understand crude oil. In 2015, "We're not really sure why this is happening. We need to study." It's absurd. There was a petroleum engineering professor from University of Texas who called them out on that and said we knew how to do this 80 years ago, "It's a simple spreadsheet: you figure out what the volatility is, it's going to ignite. This is total BS." That's what they get away with. And they have hearings and studies they fund, and they delay.

I wasn't as naive when I showed up at the 2015 Energy Information Administration, an organization in D.C. that provides a lot of information about the U.S. energy industry. They have an annual conference, and that year, the CEO of BNSF, the largest railroad moving the most oil by rail in the country at the time, was the opening fireside chat. The new regulations had come out. So, he's up on stage, with probably 500 people in the room—numerous media and people from all across the energy industry. And they asked, "What do you think about these new regulations?" He said, "They're good, except that braking thing. We're going to have to change that." He publicly said we're going to have to change that. And I was shocked.

I thought they, at least, did this behind closed doors. They effectively detailed the process they used, even if Trump had not come in and said we're just getting rid of regulations for the rail industry. I believe they would have been repealed because they had a process in place. They had Congress on their side. Much of this has to do with Congress—these regulation can be repealed by Congress. To be so brazen to say, "We're okay with this, except the one part. We're just going to get rid of that." And they did.

FARNSWORTH

Former president Donald Trump visited East Palestine. When he was doing his photo op thing and shaking hands, someone asked, "What's your message to Joe Biden?" His response was, "Get over here."

I would like you to speak to the irony of this situation, regarding the deregulation of the rail industry during Trump’s time as president. As far as I know, Joe Biden hasn't really spoken publicly about the situation in East Palestine. That's an issue. Trump is, of course, setting himself up for a run in 2024. Could you speak to the irony of Trump coming to this town, speaking to the people there, offering his condolences, and then blaming Biden or whoever for the problems that they're experiencing?

MIKULKA

It's pretty well established over the last five years modern Republicans have no shame. They will say whatever is politically convenient. The idea that Trump is there and trying to blame Biden is bold. When he came in [to office], not only did his administration repeal the modern braking requirement, they shut down efforts by states to mandate two-person crews. They said if a regulatory agency wants to put forth a new regulation, they have to remove two old ones—expressly stating this is a deregulatory environment now.

So, they got rid of those safety regulations. When they got rid of the two-person crew, their legal argument was, "Safety cannot be a pretext for inhibiting market growth," which is a long way of saying profits over safety, You can't say we're doing this because it's going to make people safer if it cuts into profits. That was the environment.

After the Lac-Mégantic accident happened, a very sharp columnist a few days after referred to it as a corporate crime scene. I've detailed many cost-cutting measures and policy issues—that accident never should have happened, but happened because of corporate policy. And that's what we're dealing with here.

I just read yesterday Norfolk Southern has a policy where if one of these rail-side indicators notices something wrong with the train—like an axel head or bearing is on fire—they get a warning, but the head office calling into corporate can override it and "keep going until you get to the next one." It's policies of putting profits over safety—that's what the Trump administration did.

They also came in and said the Association of American railroads have been lobbying for a while to move natural gas in liquefied form, known as LNG [liquefied natural gas]. It hadn't been allowed to be moved by rail, and they've been asking for it. Trump issued an executive order and said within a year, we will have a rule to allow this to happen, and did. Thankfully, it was challenged: multiple groups filed lawsuits. When the Biden administration came in, they put that on hold, which was the only sane thing to do. Because, if one of these LNG trains derails in a populated area, it's going to make all these other accidents look like a rounding error. It's incredibly dangerous.

The Democrats are also under the influence of the lobbyists; the important safety changes that were not implemented under the Obama administration were the result of lobbyists pressure, but certainly the Trump administration, and Trump himself, has no standing to be talking about rail safety in any way.

FARNSWORTH

I want to speak to the Democrat side of this, too. There was a railroad workers strike last year: an effort by rail workers to organize themselves with their unions and say, "We're not getting any sick days and being treated horribly. And if you care about this industry working and functioning properly, we need to be treated with some basic worker protections." And from my understanding, Congress and Biden basically pushed through legislation that broke the strike. When it came to bargaining with the industry, the workers really didn't get much of what they were demanding.

There seems to be numerous factors here: workers rights and the regulatory aspects to it. But it seems like no matter what angle you're coming from, whether it's from the Democrats or Republicans, there's really not much of an interest in raising the standards of the rail industry, as far as safety regulation and workers rights. Would you say that that's a pretty safe assumption?

MIKULKA

Yes, I think it is. I haven't looked recently, but the rail industry spreads money around everywhere. Some of the top donations from the rail industry go to Democratic congressional representatives.

As I mentioned earlier, it's an incredibly powerful lobby and have that ability, which came up in that whole strike discussion: if the railroads shut down, it's going to tank the economy, so we can't have that happen. What we don't and should see, in my opinion, is the government using their efforts to say, "Okay, agreed, but people need sick days."

Norfolk Southern is buying back $6 billion worth of stock. BNSF is owned by Warren Buffett's company, one of the richest people in the world. Bill Gates is one of the largest owners of one of the Canadian railroads. These are very wealthy people getting much wealthier, while these workers are being pushed.

The schedule that these rail workers are on is brutal, and then to not have paid sick days. The trains now are 25% longer than they were 20 years ago. They're trying to use fewer employees. They call it “precision railroading”— adopted like 20 years ago—which is basically business school thinking: "How can we make the most money out of this? The workers are expendable, the cost of business, and not part of this success story."

So, that was very disheartening. I've talked to a lot of rail workers over the years, and it's a tough job, and keeps getting harder. They call it “riding the elephant,” when you're driving one of these trains 150 cars long. The tracks weren't really designed for trains that long—nothing was. So, it's a real talent to be able to move one of those trains over those tracks and deal with the fact that, when you're slowing down, the back of the train is coming up on you. The workers deserve a much bigger piece of the pie than they're getting, and deserve to be safe.

FARNSWORTH

Absolutely. This reminds me of the first chapter of your book, where you write about the conditions set for the explosion of a freight line in Lac-Mégantic in Quebec. A worker had parked the train— it was at night, he was going to go to sleep. He did everything he was supposed to do. But apparently, there was a series of things that happened: If I remember correctly, there was an alert of a fire on the train, and emergency workers came to turn it off. The train then started to roll downhill, and exploded in the downtown of this small town. The Canadian equivalent of a SWAT team arrested [the train conductor] and dragged him into court. And people responded, "That's not who we're wanting to blame." He did everything he was supposed to do as a worker trained to do this job. It's the regulatory bodies, and the industry itself, that's the problem. This is as old as capitalism itself: we blame the workers versus the actual companies or the context in which they're working in. It's a pattern repeated over and over again.

MIKULKA

Yes, I think you're 100% correct, they scapegoated that employee. Thankfully, after the trial, he was found innocent, essentially. But he had to go to a big trial and go through all that. No executives paid any price for that. It happens over and over. Is the CEO of Norfolk Southern going to pay any price for this? No. He's going to get a big bonus. So, that's the situation we're in. I don't know how they sleep at night, but when they made these regulations for the high hazard trains, in their calculations, they said, "If we're running as much oil by rail as we expect to, we're going to have eight or ten of these accidents a year." That was just accepted. Everything in the regulations is based on a cost benefit analysis. So they ask, "How much would it cost to put modern brakes on these trains?" That's a number we know. And then they respond, "Well, what's the benefit of that?" We might not have as many accidents, we might not kill people, we might not contaminate the environment. Then their conclusion was, "We're not willing to, the cost is too high for that." They know people are going to die. They know they're going to contaminate the environment. They accept that as a cost of doing business.

At one of these D.C. events, there was another representative of the American Petroleum Institute, and she said, "We don't see transportation as a risk. We just see it as the cost of doing business." This is as trains are exploding—it was a real issue at the time, and were blunt about it: "We don't we don't see the risk." It's not a risk to their offices where they work. It's not a problem where they work and live. A colleague of mine at DeSmog years ago got a quote from a pipeline executive who said, "Well, I wouldn't live near a pipeline." Who would be so stupid to do that!. It's the same thing with these railroads, you know they don't live near the railroads.

FARNSWORTH

It's eerie because I actually I live in a town in northern Washington State. I'm right on the border of Canada. There's a rail line that cuts right through here, and I hear it almost every day. I sometimes see piles of coal on it or something, but I don't know what else they're carrying. So, now you look at it differently. It's not just a background noise, or just part of the background environment.

MIKULKA

One of the places I lived as a child, a train bridge almost went under the corner of our house. It was really loud. For trains, in my experience, the nuisance was noise. I currently have a house three blocks from the rail line, so I hear the trains all the time. Yes, it's annoying, but you don't realize what's actually on those.

Unfortunately, in Washington state where you are, because there are no pipelines that go from across the Rockies, it is one of the areas in the country that is still getting Bakken oil trains, because there are five refineries in Washington State. And they love the Bakken oil, because it's cheap, and mix it with Alaskan oil that they also get. And actually, they mix it with tar sands oil to approximate the Alaskan oil that they used to use more. Washington State is one of the few destinations that still has a regular supply of the Bakken oil, which is just as dangerous as it's always been. I believe it was in Washington and not Oregon, but a train separated and a couple oil tankers caught on fire in a town, but it was going slow. Thankfully, it was like 20 miles per hour, so it wasn't a major disaster.

FARNSWORTH

That's news to me. Great to know.

I have one final question, in reference to being a journalist in this environment and covering this subject. When looking you up, there was an article published by The Intercept in 2020 titled Amid terror warnings, railroad industry group passes past intel on environmental journalists to cops:

The reports singling out Mikulka alongside neo-Nazis and radical Islamic terrorists were included in a series of slide presentations prepared by the Association of American Railroads and distributed to member corporations — as well as to law enforcement. Described on its website as “the world’s leading railroad policy, research, standard setting and technology organization,” the AAR is an industry trade group representing the political interests of the railway business in the United States.

Over the last couple of years, Mikulka and his reporting were featured in at least four separate “Railway Awareness Daily Analytic Reports (RADAR).” Mikulka’s friend found the documents the same way The Intercept did: as part of a trove of documents dubbed “BlueLeaks” that was hacked from so-called fusion centers — regional clearing houses coordinated by the federal government for the purposes of sharing information — and published by the transparency collective Distributed Denial of Secrets. More than two dozen RADAR reports had been stored by two fusion centers, the Maine Information and Analysis Center and the Southeast Florida Fusion Center, along with dozens of additional security reports authored by the AAR. (The fusion centers declined to comment.)

The RADAR reports serve as a poignant example of how the private industry group collaborates closely with public law enforcement agencies, assisted by a national network of fusion centers. The intelligence hubs were designed to bring local, state, and federal law enforcement and security agencies together with private businesses to share information about potential threats. The BlueLeaks documents provide a picture of a system capable of transforming a threat to a corporation’s bottom line into a security threat to be addressed by police.

It's describing the connections between public law enforcement agencies and private industry groups. I saw the PowerPoint slides of a presentation showing various threats to the security of the railroad industry and rail lines—again, Neo-Nazi groups, fundamentalist radical Islamic terrorist groups, and you.

Obviously, it described what you felt when you found this out. I'm not saying they think that you're an actual material threat to their ability to do what they're doing in the same way terrorist organizations are by attempting to disrupt the infrastructure of the United States. But, you're obviously making enough of an impact with your reporting that they are concerned with what you're pointing to and revealing in your investigative reporting.

I want to get your thoughts on this and your general sense of environmental journalism right now. By attributing what's happening in East Palestine to deregulation, the rail industry actually sees your work as a threat. Also, what about law enforcement’s involvement? It's quite a trend, and a disturbing one at that.

MIKULKA

Understandably, it's disturbing. It shows, again, I was a little naive going into all of this. I was not expecting that development. But it shows that not only are the corporations directly involved in the regulatory process, but they're directly feeding information to law enforcement.

I believe what I said in that article was they can attack what I'm saying, because I'm right. If they could discredit me, they would. I wrote 100 articles and a book, and they never found an error. So, what's the next best thing that I can do? Try to discredit me, take me out of the picture some way. There certainly are radical environmentalists and examples of people trying to sabotage infrastructure. That's not unheard of. But, obviously nothing in my work suggest that's a smart thing to do, or something you should do. It was a huge leap they made, because they said people interested in environmental issues read my work, and so that somehow made me the threat. It's very disturbing.

The industry has disdain for the public. They really do. They think they should be above the law, essentially. And in many ways they are. Did anyone from the Association of American railroads ever contact me and say, "We'd like to talk to you about this”? You think that would be reasonable. "We have some concerns about your work." No, they just go to this ridiculous stretch of lumping me in with Neo-Nazis. And so, yes, I think it's very disturbing, and I think we'll see more of it.

I don't know all the details, but, I think in Minnesota at one of the pipeline protests, the pipeline companies are directly paying the police to be involved and go against the protesters. It's another consolidation; they're certainly too powerful. What we need are politicians who are willing to stand up to them, and what we get is grandstanding from people like DeWine and Trump. DeWine has taken a lot of money from the industry, and has a good friend who used to work for Norfolk Southern. We get a lot of lip service, but when it comes down to it, these corporations are really calling the shots.

And the fact I was making such little money writing for an online publication that most people have never heard of—it’s not like I was running those articles on the Wall Street Journal front page. But even that is something they had to use these absurd measures—I don't know what they were hoping would would happen, that I would get arrested? Really, I don't know what the outcome was they hoped to achieve. It's ridiculous it's happening in America, where we're supposed to have a free and open democracy, free speech and free press. It's chilling.

I still occasionally write, but I've moved into a different job now, so I'm no longer working as a journalist. I look at some of these articles that my fellow journalists are writing now and think, "You might be on the list now, too."

FARNSWORTH

There are a lot of ways to interpret this. In some kind of twisted way, you should be commended for being acknowledged for being a truth-sayer in this regard, because if people were to look at your body of work, with all the articles and book you've written and everything that you've done over these years, there is such a concentrated amount of work there. If anyone has any questions about how the railroad industry works, how deregulation has occurred, and all the threats that come to public health and public safety, they just have to look at your body of work. I'm not trying to downplay how freaky it is to look at that and see yourself lumped in with terror cells,

MIKULKA

Certainly a badge of honor. It means they were paying attention. Actually, something happened yesterday, not completely unrelated. With my current work, I'm doing some work on the field of hydrogen. And there, unfortunately, history is rhyming.

What happened with the bomb trains and oil trains was fracking unleashed a bunch of oil in North Dakota, and there were no pipelines, because no one had been producing oil in North Dakota. What they did was take a bunch of tank cars designed for molasses and corn oil, and string them together and fill them with oil and started running them across the country with no new regulations—nothing. That's why these bomb trains happened.

In this whole push for hydrogen development, North Dakota is trying to use their natural gas resources to make hydrogen. And the BNSF has signed an MOU [memorandum of understanding] with this company to say they’ll move their hydrogen by rail. It's the exact same thing. They're producing this stuff away from the rest of the country, and need to get it to where it will be used. I am strongly against the idea of moving large amounts of hydrogen by rail. I'm a firm believer that we're going to need green hydrogen, not hydrogen made from natural gas, but clean hydrogen as part of the energy transition. That's a big focus of my work, and I've written about that as well. But we're seeing the same thing happening.

So, I called up the FRA yesterday and asked about what they're going to allow. The guy at the FRA said, "You used to write for DeSmog, didn't you?" It's not a big world, the rail world, but DeSmog was very good about allowing me to follow the story until it was done. Most journalists, after the trains stopped exploding and got into the regulatory process, stopped covering it. So I was able to really follow the whole thing, complete it, and really tell the whole story. And, unfortunately, we're talking about this now, again, because of another disaster, which was entirely predictable. It's just a numbers game. This will happen again.

Justin Mikulka is a research fellow at New Consensus working on investigating the best solutions and policies to facilitate the energy transition. Prior to joining New Consensus in October 2021, Justin reported for DeSmog, where he began in 2014. Justin has a degree in Civil and Environmental Engineering from Cornell University, and is the author of Bomb Trains: How Industry Greed and Regulatory Failure Put the Public at Risk (2019).

Excellent interview - documenting a terrifying scandal in detail.