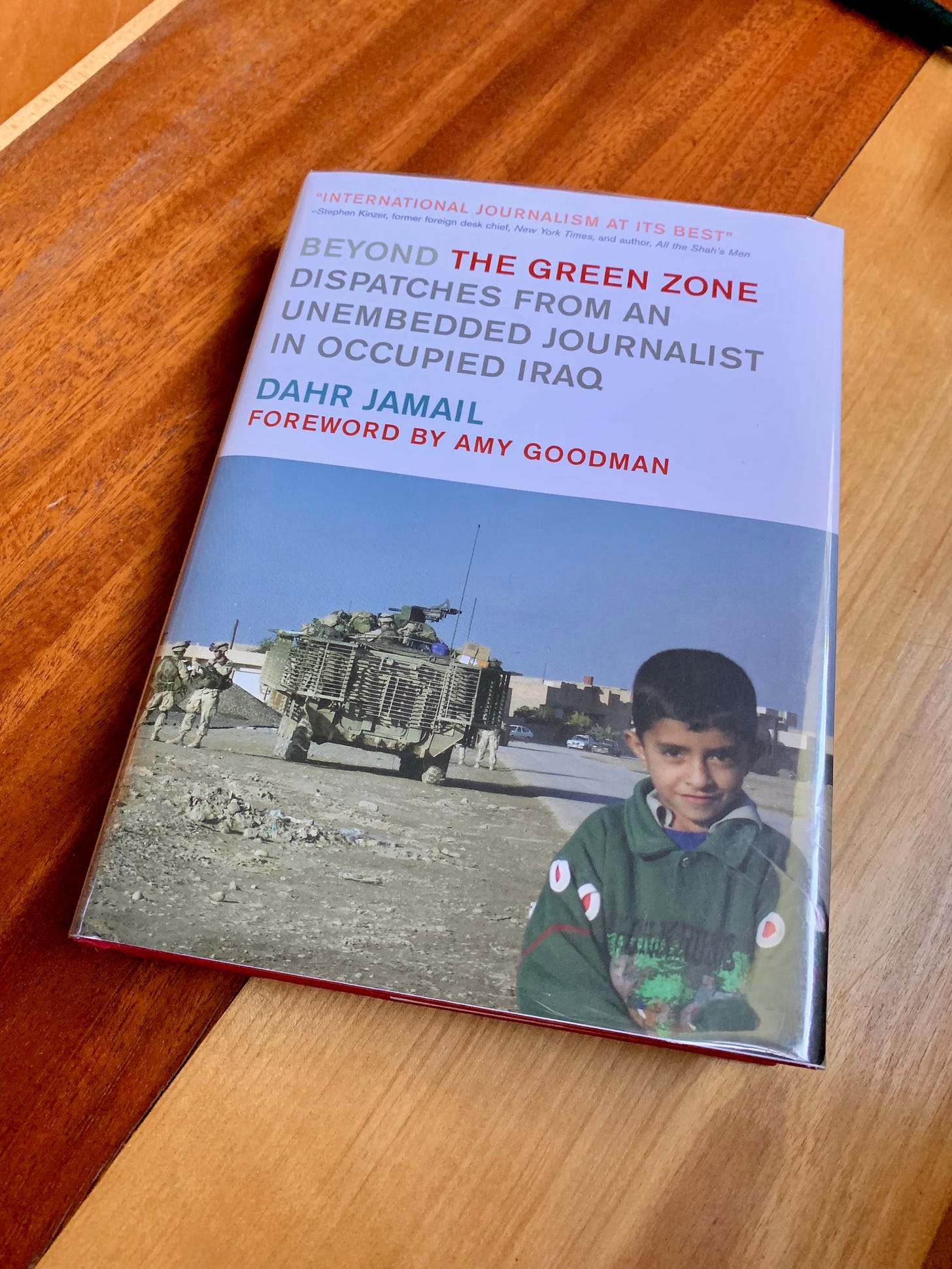

Author and former climate journalist Dahr Jamail returns to the podcast to discuss the 20th anniversary of the invasion and occupation of Iraq by United States-led coalition forces. Jamail began his journalistic career as an unembedded journalist documenting the war from the ground beginning in 2003, highlighting the countless war crimes committed by the occupying forces against the civilians of Iraq, superbly documented in his first book on the subject, Beyond the Green Zone: Dispatches from an Unembedded Journalist in Occupied Iraq published in 2007 by Haymarket Books.

Dahr and I begin our discussion by reflecting on the atmosphere in the United States in the ramping up to the invasion of Iraq, 20 years on. In an effort to convince the population of the United States, and by extension the global population, the Bush Administration promulgated alleged concerns of “weapons of mass destruction” in Iraq and connections between Saddam Hussein, Al-Qaeda, and the infamous events on September 11, 2001. It was laden with propagandistic narratives founded on a web of lies.

Prominent media outlets played along, living up to Noam Chomsky’s observation that “[p]ropaganda is to a democracy what the bludgeon is to a totalitarian state.” From the outset, Dahr Jamail understood on an intuitive and intellectual level that the lead-up to the overt military incursion and occupation of Iraq was deeply unjust, and would lead to horrific outcomes, especially and primarily for the people of Iraq. In his restlessness to seek and share the truth on the matter, he leapt into the fire and cut his teeth as a reporter by becoming one of the few unembedded journalists to bring the day-to-day experiences and voices of Iraqis to the forefront for Western audiences. As his reports began to gather a wider readership, the conditions in Iraq swiftly deteriorated, and whatever patience or goodwill that was initially extended by Iraqi citizens toward the coalition forces inevitably curdled into widespread rage and insurrection. In Beyond the Green Zone, Jamail documents the horrific crimes committed by the occupiers and their corporate contractors as they arrogantly and recklessly destabilized Iraqi society in every imaginable way, waging vicious campaigns of collective punishment, torture, mass murder, and lasting environmental degradation.

It became commonly stated during the rise of Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential campaign that we’ve now entered into a post-truth era, that our collective sense of reality had become fractured and poisoned by cynical political actors intent on attaining autocratic power by compulsively lying about everything of consequence under the sun, repeating “alternative facts” ad nauseam until a desired result was achieved, often with disastrous consequences. But, as Dahr reflects on in this discussion, truth and facts are always the first casualties in war—no war can be achieved without lies and propaganda. And twenty years on from this invasion, many of those initial lies survive in various guises in U.S. media coverage. Rarely do the stenographers of Empire own up to their complicity in warmongering. In the last decade, George W. Bush received a PR makeover and now sells books of his shitty paintings and cozies up with Michelle Obama for photo-ops, while the decrepit Dick Cheney calls Trump a “coward,” saying, without a sense of irony, that “there has never been an individual who is a greater threat to our republic than Donald Trump.” Upwards of a million dead in Iraq as a result of the war. The largest expansion of domestic surveillance and erosion of civil liberties in a century. Given enough time, mass murderers can be reformed and granted legitimacy under the right circumstances in the United States.

Ultimately, this discussion is a rumination on truth—what it means to seek, demand, and advocate for it despite the personal costs incurred. As the situation darkened in occupied Iraq, Dahr had to find, in his own words, a “deeper moral motivation to do the work” of reporting on the reality of the situation, as most of the prominent media outlets in the U.S. continued to refuse to report on the subject honestly. As his journalistic and writing career evolved over the years, this deeper moral motivation carried over into his integral coverage of climate disruption and biospheric disintegration, and persists in his current work highlighting the perspectives and voices of Indigenous peoples in our time of deepening crises and collapse.

Personally, I’m honored to have known him over these years and to have interviewed and conversed with him on these subjects numerous times, to witness the various iterations of his relentless drive to speak to the heart of things.

This interview was recorded on April 4, 2023, and released as episode 345 of Last Born In The Wilderness. The transcript that follows was edited mostly for clarity, and somewhat for length.

PATRICK FARNSWORTH

Thank you for coming on the podcast again. I actually thought that this wasn't going to happen, in the sense of you coming on again. There was nothing wrong with that, of course, but I assumed we had spoken about what we needed to talk about on this podcast, and that you reached a point in your career that my interviews with Dahr more or less ended. So, it was a bit of a surprise that we're coming back to this again. I'm pleased that you are back on. Thank you for doing and considering it.

DAHR JAMAIL

Thank you, Patrick. It's really great to be back on in this capacity, and actually the timing feels perfect. Especially with this topic, it feels like a real full circle, and I'm sure we'll get into that. I've gotten very selective in doing any interviews, and it felt right to have this conversation with you for the public at this particular time, and least in my own personal trajectory. So, I'm grateful that we have this chance to talk.

FARNSWORTH

Yes, of course. What we're going to go over is in large part your first book—that's the central topic or at least the beginning point for this discussion.

Sometime last year I was in a small town, and they had this really excellent bookstore, and I went down to the journalism section there, and behold, your first book, Beyond the Green Zone: Dispatches From an Unembedded Journalist in Occupied Iraq was just sitting there—a beautiful hardcover edition, practically brand new. This book was published in 2007.

Speaking to when I first met you, which was some years ago, when you were still writing for Truthout about the climate and environment, that was the Dahr that I knew: the Dahr that was writing about the climate crisis, the depths of the kind of spiritual and philosophical questions that arise from that, as well as the data. And then, of course, your book that came out, The End of Ice, in 2019.

2020 was the last time we spoke on this podcast, discussing the anxieties and tensions that were coming up in the election period of that year. In that last interview, we did mention your time in Iraq. And so, when you mentioned this full circle, I would agree. This is, admittedly, as an interviewer, something I really wanted to get into with you at some point.

I started reading your book about a month or so ago. It was a coincidental thing that it just so happened to be around the time that the war in Iraq began. I've mentioned to you privately that it's an incredibly important piece of journalism, providing an accurate view on the ground of what the people of Iraq were experiencing during the first year-and-a-half or so of that occupation. The voices in that book are the people of Iraq—that's who was speaking. You occasionally quote things from the mainstream press or what the military officials were saying at the time, but really just to contrast what bullshit was being propagated at the time.

It felt, as I was reading it, I was descending through the circles of hell, going further and further down into some of the most horrific things I could imagine a person experiencing and witnessing, and you did it as a journalist.

So, I described this to you, and I really sincerely asked if you would be willing to have a conversation about it, considering it is the 20th anniversary of the beginning of this war and occupation. And so, here you are.

How do you feel about this book and your time in that place? Again, there's been so much time since then, but I'm curious what your general impressions and thoughts are about your work at that time?

JAMAIL

I would start by talking about why I went.

I got politicized a bit later in life than many folks, which for me meant it wasn't until my mid-20s when I started to really do a lot more reading and critical thinking about the government, the history of this country, and its role around the world, and all of that was in motion leading up to the war in Iraq. There was this pressure building inside, and the more I read, the more furious I became, and felt responsible as a citizen of Empire, living in the bowels of the machine, to do something. I didn't know what to do, just like I think so many other people during the build up to the war. I was feeling that pressure, angry and frightened of what was to come, and something in me snapped.

I had a good friend whose daughter was working with the International Solidarity Movement in Palestine, and I was reading what she was sending her mother: these really personal, raw, well-written diary entries of each day of what she was seeing. I just knew that I wanted to do that, and it was something that I could do because I'm a writer, and threw myself into Iraq.

The invasion was launched in March 2003, and within a few months of listening to it on the radio and reading about it in mostly international media, I decided to throw myself in. And that was something that I could do, go over there and see with my own eyes and write about it because I was outraged at the level of propaganda. I took it really personally—in retrospect, I felt like, at least at the time, that was something I needed to do. I was just so angry, outraged, and desperate to try to do something, and was in a position in my life where I wasn't married and didn't have any kids. If I wanted to put my ass on my line on the line, I was free to do that, and didn't have other responsibilities. I threw myself in, and I felt like it was absolutely necessary and worth it for me to do it.

I just thought I would go and write about it. I basically took money out of my savings, and had a laptop, camera, and notepad, and thought I’d go for about three months because that's what I could afford. I stayed in a super cheap hotel and sometimes shared rooms with folks, doing it on the cheap to stay as long as I could, and started sending back email dispatches to folks. By the end of that trip, I was starting to get hired to work as a journalist. And then I thought, I guess I can do this, and then it just continued.

I don't want to get lost too into the weeds of that story—I've told it far too many times. But personally, I had no choice—there was this fire in me. I had to go. People tried to talk me out of it, and that was not going to happen.

FARNSWORTH

That was the next thing I wanted to discuss. I imagine there are two levels to this, which is to remind people who were alive during that time and for those that were too young to remember or hadn’t been born yet because it's been 20 years ago now. So, certainly, a generation is growing up with having not remembered 9/11 or that invasion, or lived through it.

Remind us of what the atmosphere was in the United States was at that time. There was so much propaganda—it's easy to forget because it kind of went away. Went away is not the right way to say it. Instead, it’s like the veil was lifted slightly: people kind of acknowledged at some point, 20 years on, that it was a bit of a disaster and an awful thing happened. They might have all kinds of rationalizations about it, but some of the initial stories and narratives that were being constructed and pushed in everyone's face were so blatant.

That was a hell of a time to decide to do what you did. How do you remember that time? How do you remember what it was like for people to hear you say you're going to Iraq to talk about it from the ground as an unembedded journalist?

JAMAIL

The level of propaganda was so intense. Literally, you could turn on CNN, and there would be a graphic of the outline of Iraq, and then transposed over it is a photo of Saddam Hussein with a big bullseye on him. That was the lead, and then "let's bring in the news." Gee, I wonder how they're going to talk about this war? A high school kid could make better propaganda. But if you're going to dumb it down to the average news consumer in the country at that point—it's worse today, of course—then that's what you have to do, and that's what they did.

But it wasn't just CNN and the usual suspects—corporate media, of course—it was also the New York Times with the famous stents they did with Judith Miller and other op-ed writers. It was really just a level of propaganda that I found, personally, deeply insulting. It was almost as though if you turned on any of the mainstream news during much of the build up, it was like an arms manufacturer show, with detailed, computerized versions of cruise missiles, showing all the specs, and then videos of them going into buildings and such. It was an orgy of war weapons, celebrating violence and the might of the US military, with no facts, and no critical thinking.

If you read that news, and then held it up against what, for example, was being reported in The Guardian or The Independent at the time in the UK, or other international media—English-speaking or not—there were two entirely different stories. There were never weapons of mass destruction or a link to 9/11 or any of this, and yet that was being trumpeted out in the corporate press, ad nauseam. There was a parroting of the Bush administration propaganda that was practically verbatim. The White House didn't need its own press corps at the time, they didn't even need a spokesperson because the corporate media did it for them. And even though huge numbers of the people in this country opposed the war—that was evident that February before the war was launched with the record-breaking protests globally—it went on.

The level of propaganda was really mind-numbing, and really had my head spinning at the time. And then you look at what's happening today with the 20th anniversary coverage. It's a tepid admission in some cases of, "this was a horrible mistake and a tragedy for the Iraqi people," but it's been dramatically softened.

Even much of the left media still lowballs the figures of dead and displaced Iraqi people. Most of the left media still only reports it was 300,000—a figure I was seeing—and entirely ignore the second Lancet medical survey, which put it pushing a million, and it's well over a million at this point according to other surveys. That's just one example of this continuing to downplay "the mistakes" of the Empire.

This was a deliberate war of aggression to try to just take control of a country to get its resources. It was a gross violation of international law. And it was, at that time, the most egregious example of what this country does when it hasn't ever come to terms with the genocide of the Indigenous population that lived here, before this country was formed. It hasn't truly come to terms with the slavery that built much of this country. If it hasn't come to terms with those, and until it does, it's going to keep projecting that outwards, and Iraq was, at that time, the most egregious example of that.

So, it really turned my stomach to see a lot of the 20-year anniversary coverage, even a lot of the so-called left leaning media that didn't go nearly far enough in talking about what was done in Iraq, in the way that it deserves to be discussed.

FARNSWORTH

It seems that much of the time it's reduced to the economic impacts, that it was an extremely expensive war and put the U.S. in an enormous amount of debt. Often, if we discuss casualties, it's about the U.S. or coalition forces that were affected by basically occupying this sovereign country.

Once you were in Iraq reporting on the ground, and as things began to disintegrate over time, how did the U.S. media continue to report on the situation there? One of the most egregious examples that come to my mind was when you were reporting on the two sieges of Fallujah and the crimes that were committed by U.S. soldiers that were not being reported in the U.S. media. There were certain aspects of what was happening on the ground that were also part of the continuation of the propaganda that was so egregious, even in comparison to the initial forms of propaganda that tried to get the population's support for the war. It was such a disparity and really striking.

What are some examples of what Iraqis were actually experiencing versus what the U.S. public was being told?

JAMAIL

You're right, Fallujah is a great example.

I broke the story during the second siege of Fallujah of the U.S. military using white phosphorus there, which is a weapon that is illegal to use under international law in a place where there could be civilians. The Pentagon, at the beginning of that siege in November 2004, admitted that there were up to 35,000 civilians in Fallujah, but there were far more than that. They even admitted to that and then went on to use this weapon. So, that's an egregious violation of international law.

I reported on that story, and talked about it on a lot of the left media that I was doing radio and TV reports for at the time, and then it came and went. And there are many other examples that I'll talk about, but long after that siege happened, the mainstream media in the U.S. wouldn't touch it with a 10-foot pole because it's a war crime, and they're among a heap of war crimes that the US military committed in Fallujah, in that siege and in the first one in April.

Years went by, and I came across a book by a photographer, Ashley Gilbertson, who was working with the New York Times. He was working with New York Times reporter Dexter Filkins, and they were embedded with the military and went into Fallujah during the November siege. In that book, he wrote about being with Filkins and the whole New York Times crew and at times having little fragments of white phosphorus falling on their backpacks. And so, you've got a New York Times reporter with little pieces of white phosphorus falling on his backpack, and that of his photographer, who never reported it. That I think says so much about the corporate media's role, not just in the selling of the war, but then the soft peddling of the occupation.

Meanwhile, this was a siege that I saw with my own eyes. Mass graves had to be dug in the aftermath with bulldozers filled with bodies of people that were killed. There were no discerning civilians, fighters, women and children, etc., just like in the April siege, where I saw with my own eyes women and children who had been very recently shot by snipers who were shooting everything in the city. I watched a young boy bleed out on a table as Iraqi doctors worked to try to save his life. Women and older folks all around the city, at different times, coming in saying the same thing: that you couldn't leave your home, or you would be shot. I had friends who went out into in an ambulance to try to pick up wounded people or dead bodies—they were Westerners—and the ambulance was shot, and they had to duck down into the floor of the ambulance and barely made it out alive, and were lucky at that.

Collective punishment: all water and electricity was cut in the city for both sieges. No medical care was allowed in, and no wounded people were allowed out during those sieges. Any of what happened was underneath the radar. Those are just some broad brushstrokes. And then, of course, there's Abu Ghraib: torture, humiliation, beatings. Iraqi prisoners being sodomized with broom sticks, things like this.

This is what the Empire did in Iraq, just off the top of my head.

FARNSWORTH

There were several points in the book where it became obvious that you had an indication of some broader, deeper crisis. You mentioned Abu Ghraib. Earlier on in the book, you had been notified about a man who was in a hospital who had been tortured to the point where he was in shock—I don't think he could speak or hardly move at all. He was obviously the victim of torture.

You mentioned you tried to feed this information to larger media outlets in the U.S. that this was happening. You definitely were trying to get this information out there and gave them a lot of information.

JAMAIL

I was naive enough to think that would have been a success. That really just shows how naive and overly idealistic I was. I was just trying to get the truth out there in any capacity. I didn't care about my name, money, or any of that. I thought, people need to know this. I really genuinely believed that if people knew better, they would do better. That was one example.

But yes, this man, Sadiq Zoman, was a Ba'athist, and was captured and basically beat into a coma, and then given back to his family, and there was nothing that they could do at that point. I was amazed that you had doctors' reports, photos of him, had gone and sat with him and his family and wrote up the story, and then just thought, "If we're going to pretend to be a country that adheres to international law, and paints itself as the good guy, then we've got some things to answer to." And it was really a fool's errand. It obviously didn't pan out.

But that, along with so much of the rest of my reporting, I hit a point where it did become clear that this was not going to change the situation. It wasn't going to stop the occupation. I was exposed to that quote from the famous Israeli journalist Amira Hass, who did very honorable reporting from Gaza and the West Bank for decades. Someone at one point asked her, "Why do you keep doing what you do? Things only keep getting worse, year after year, decade after decade," and she said, "So that at the end of the day, when history is written, no one will be able to say that they didn't know. No one will be able to say, nobody told us this was happening." That became my de facto motivation for, from fairly early on, when I became extremely dispirited seeing story after story come to pass and nothing changed, only to get worse.

I had to find a deeper moral motivation to keep doing the work.

FARNSWORTH

I can see how that would have also led and informed you when you got to the point where you left behind that type of reporting, and started covering the environmental and climate crisis. It's pursuing the truth for the sake of knowing it.

I want to pivot to a discussion around truth, and there are a few levels to this. There's the level of, now that we're two decades on from this invasion and occupation and the kind of consequences of that, the legacy of what this war effort has had on our concept of truth in the United States.

Now, certainly, we can go back even further and see the ways in which truth is something of a social construct, and what is considered the truth in the U.S. context has always been fantastical on some level, or illusory. But, we have had instances where the truth, due to intrepid journalism, has broken through some of those illusions, and certainly, on some level, played a part in the shift in the public consciousness around the war in Vietnam, for example.

But I think the war in Iraq is a very particular example, and I want to appreciate how the trajectory from 9/11 to the war in Iraq and to the present moment impacted our understanding of truth.

Trump was elected and lied compulsively about everything, flagrantly, with no shame. He still does, of course, but people described it as if we entered into the post-truth era, that somehow truth died. I think it died a long time ago in this country.

This is true especially with what you experienced leading up to the war, your decision to go and report in Iraq, and the ways in which the truth that you were reporting from there was not being picked up by the media outlets with the larger audiences. I'm curious about this concept of truth and how you feel about this idea that we're in a post-truth era now, and how this relates to your reporting in Iraq. How does that hit for you right now?

JAMAIL

That's a very interesting point. It's interesting because your question really confronts this year zero mentality of whoever coined the term of being in a post-truth era because, as you point out, I can't think of a war the U.S. ever got involved in that wasn't based on a lie. We can go back much further than Iraq or Vietnam, even to when the U.S. decided to enter into World War II. There hasn’t ever been much truth involved when it comes to the U.S. government.

Plenty of people have made comparisons to Vietnam and Iraq, at least during the hot war that was going on. The Vietnam War began with the Gulf of Tonkin incident, also based on another lie. The Bush administration used the events of September 11 to build momentum for the propaganda effort for the invasion of Iraq. While certainly truth was already a casualty at that point when it came to the U.S. government and the corporate media, I would say that the Iraq War was a pretty significant erosion of whatever may have been left of the foundation of truth in that realm of the media in this country. Any pretense of legitimate media not being military or White House stenographers was gone. The level at which they adhered to the government line was precisely the level at which they had abandoned reality. And that really, I would say, didn't by itself set the stage for this era that we're in today where it's exponentially more off the charts, but it certainly played a significant role in creating the conditions where people became increasingly normalized to untruths and coming to expect this instilled cynicism, and that anything coming from the government will not be true, which a critical newsreader already knew.

As the great journalist Martha Gellhord said decades ago, "All governments are bad, and some are worse." Any thinking person understands that all governments lie, it's just some do it far worse than others.

But all that is to say that the egregiousness of the war in Iraq, with more than a million Iraqis dead, and more that continue to die in instability, violence, and despicable living conditions across that country, with millions displaced internally and externally in a country that's essentially a failed state today—all that has been thrown into the dust bin of unmemory of the dominant culture in this country. I would argue that things wouldn't be as bad today on these fronts if it weren't for what was done in Iraq, and how that was set up to be perceived by the American public by the government and the corporate press.

FARNSWORTH

Yes. I think there's a way I can draw a connection and segue into what is more of a personal point. Knowing and having known you for these years, reading Beyond the Green Zone, I imagine you were about my age, mid-30s, during that time. There's about a 20-year difference between us in age. So, imagining you at age 34 or 35, with the knowledge that I have of you and my relationship with you, I could hear your voice as I was reading it.

What's incredible about the book is it’s a fine piece of reporting, but there are moments where you take asides to write, "At this point, I was so beyond burned out. I was fried. Every time I heard an explosion, I would shake," describing the scene, mood, the feeling you were in at that time. Describing how, I think you were in Iraq at three different spans of time.

Is that correct?

JAMAIL

Yes, for the first book, that entailed three different trips.

FARNSWORTH

At certain points, you either went back to the U.S. or went to another country, like Jordan. You described the trauma of that experience. Anyone who witnessed what you did, of course, would experience PTSD. I want to talk about this very particular form of trauma because it has to do with this idea of truth.

You were able to leave—you had that ability—and had a certain privilege that people in Iraq really didn't have. You could fly back to the U.S., and when you did, I could only imagine what that must have felt like.

To have just left, basically, what was the spear tip of the occupation, of what the U.S. Empire actually is in all its ugly truth, and come back to the belly of the beast, to the womb of the United States where it's relatively safe and comforting. Everyone's going to their jobs, and functioning on some sort of institutional and infrastructural level that you just couldn't have in Iraq. And then, you decided to go back.

There's a particular kind of experience there that I would ask you to speak to because I think it speaks to this idea of truth on some level. What felt true and real, what was actually in reality, even with all the comforts of modern U.S. life in 2003-2005. You felt, "No, I have to go back." Could you speak to that?

JAMAIL

Yes. I was experiencing what so many soldiers experience. I don't use Iraqis as an example because, as you pointed out, importantly, they couldn't leave. If you had an Iraqi passport your ability to travel was extremely limited, to put it very diplomatically. So, I’m talking only about my experience and people who could freely go in and out of the country by choice.

I had been shot at. I had bombs go off adjacent to my hotel, blow my windows out and my door in, and part of the ceiling fall down on me. I had been temporarily detained a couple of different times by I’m not even sure who the people were. I definitely had plenty of trauma in addition to seeing really horrible deaths and what had been done to bodies, etc. As horrible as things were in Iraq and as traumatizing as it was to experience what I had, it was real.

I remember coming back to the United States after six months to a year into the occupation, after my second trip into Iraq, which was when I went into Fallujah in April 2004. It was an extremely intense two-month trip. I saw a lot of shit, and was in several really dicey situations. And then, two days later after coming out of Iraq, I'm in Manhattan with the folks I was writing for at the time, staying with them in their apartment, and they were running this little progressive news website.

It was like coming into the matrix, as you describe, with people just asking things like, "Hey, what do you want on your pizza?" Iraq didn't exist. And I remember at one point I went and sat on their fire escape and just started smoking cigarettes. I don't smoke, normally, but during Iraq, I smoked like a friggin' chimney. I went out there and just started chain-smoking.

I was reading news about what was going on in Iraq from some sources that I trusted, and couldn't wait to get back. I just didn't fit in anymore to this culture based on denial, lies, superficiality, rampant materialism, and consumerism. It was absolutely crazy making, and I was in severe PTSD. I couldn't really feel anything beyond numbness and rage—kind of typical, like what you hear from veterans. I wasn't really aware at the time of how bad a situation I was in psychologically. I just knew it made a lot more sense to be back in Iraq.

It was really hard because you have to live with, if you choose that line of work, that unresolvable disparity of I being able to leave. My interpreter, his family, all my other Iraqi friends and people that I knew and cared about and had become very close with couldn't leave. I can remember distinctly getting on that plane at Baghdad airport and flying out, and feeling the relief of getting out of the hell and the danger, and then simultaneously, the guilt and the shame that I got to leave—it's not fair, it's not right, and it's not just. I carried all that in me, and I think part of me will always will. It was an unresolvable situation then, and I would say that it still is to a large extent.

I have a couple of different Indigenous elders in my life, and one of them is a hardcore Vietnam War veteran that was on long-range patrol in Cambodia when we weren't in Cambodia. People had a lot of friends die right in front of them. He lives with his wife in a tiny village in southern New Mexico, and it's good because things probably would not go down well if this guy had to live in a heavy population center. I really identify with him in that. I live in a house by myself in the woods in on the north coast of the Olympic Peninsula. I describe that sometimes and say, "Yeah, but I do that for a reason."

Part of PTSD, at least for me, is an agoraphobia—crowds make me nervous. I've been really close to car bombs. I've been stuck in intense traffic jams when car bombs were going off daily in Baghdad, and it makes you crazy and paranoid. And so, I still don't really like that. There are certain parts of it that you just learn to live with.

That increasingly becomes a crazy making experience when we live in this dominant culture where, back to what we were talking about, the average person has no idea what went down in Iraq, and that's a real shame. Until people can really come to terms with that, and what it means to live in this country that has done that, in our hearts and intellectually, and again, going all the way back to the genocide of the Native Americans here—if you personally ran around and killed someone, and then never made amends, never felt guilt, you'd be a sociopath. You should be locked up.

How can you not say that about the government in this country?

FARNSWORTH

Yes, what happened in Iraq is actually not unique. When you look over the history of the United States, it's full of war, conquest, and colonization, both internally and externally. What happens outwardly happens inwardly as well. And for the settlers to, I suppose, cope with what was happening, where Indigenous populations were being displaced and genocided—if you can pull that off, then you can do that to anyone else around the world, and that never gets resolved. Abstractly, we can imagine what that would look like. What does true decolonization really look like, in the truest sense? Not metaphorically, but literally.

Knowing you as a person for these years, reading this book was looking into something that seemed to have shaped you on such a profound level. It's like reading the diary of a friend who survived a war zone—that's what it kind of felt like, in a way. It has the quality of a memoir as much as a piece of journalism.

I was just thinking about when you described coming back to the U.S., and you went out to the fire escape while your friends were doing whatever they're doing, and you just chain smoked—I used to smoke, and I get the addictive aspect of coping with uncomfortable feelings or traumas. I just wanted to comment on how remarkable it is to me that you did come out on the other side of this the way that you have 20 years on. I don't want to just say commendable—it is on some level—but it is also just remarkable. And you kept on going for a long time and had a stamina to keep writing and speaking about the climate, for instance, in a way that didn't shirk away from the truth.

I see you in a different light as a friend.

JAMAIL

I appreciate that, Patrick. It really felt right to speak with you in this capacity at this point around the Iraq issue and about my experience there because you're a friend, and I've always appreciated how deeply you think and feel about the topics that you put your gaze on. That's an increasingly uncommon thing in the dominant culture to find people who will stop and dive into something and really think long and hard about it—feel it, struggle and wrestle with it, and ask the hard questions.

I think it's essential for all of us to do that, to learn and make changes. God knows that when I came back, for many years my personal life was a disaster, which, again, is very common with war correspondents or soldiers. You're not stable and emotionally available, and make consistently bad personal decisions because you're a deeply soul-wounded person. It took many years, and plenty of different techniques of healing, to finally come back to being human.

And I can say that—it's interesting, again, that we are just past the 20-year anniversary of the invasion—it really took me I'm up until fairly recently to be in the healthiest place I've ever been in my entire life. As of a little over a couple of years ago, I finally met my life partner, and that's a big part of it—having someone that I can just share everything with, no holds barred.

But even before that, having different elders in my life, two of them Vietnam era veterans that really took me under their wing and kept talking to me about PTSD. I'd call them and have these long rambling conversations, and then after a while—I can be slow with this personal stuff sometimes—I thought, "Why do these guys keep talking to me about PTSD?" And then it finally dawned on me. "Oh."

They're both Indigenous, and one of them pour sweat lodge, and I was extremely lucky to get to sit and sweat with both of these men. They decided to have that for me, for my PTSD, and that was a real pivot point and set in motion a change of circumstances that then came to fruition over time a little bit later. I had things like getting to do intensives with Joanna Macy—really profound healing experiences that over time eventually brought me to a place where I had to find a way to get more comfortable living with PTSD. It's not something that goes away, we have to live with it. That really was practice from the war zone, and now with an experience that all of us who are really paying close attention to what's being done to the planet and the ramifications of the climate crisis, biological diversity and habitat loss, pollution, and growing fascism—all of what's often referred to as the polycrisis now. It's traumatizing to read the news on any given day, if you're really reading what's actually happening. I'm not talking about CNN—I'm talking about real environmental news. Listen to what Ruth Ben-Ghiat has to say about the fascism movement in this country—real news. It's deeply traumatizing. How do you hold that gaze and stay a sane, healthy, balanced human being at the same time? It's a balancing act.

It's taken me, I'd say, 20 years to get to where I am. I can't say I've got it figured out, but I've gotten much better at it. And that's something that I think all of us, especially anybody involved in doing work for the planet and her people, have to find a way to do sustainably, or you're going to have to walk away.

I had an old friend of mine in Anchorage, when I used to live in Alaska. I came back from the occupation from one of my trips, and I would sit there with my hands in fists and was a ball of rage. He just took one look at me and said, "Bubs, you're going to need to find a way to do this without the level of anger that you have, or you will have to walk away." I didn't walk away for a long time, but eventually, I did have to step out of it for a while and then find a way to come back into reporting in a good way.

We live in this broken, dying world, and it's really hard to watch what's happening. And yes, finally, Indigenous people in this country are getting more recognition and acknowledgement, of knowing we’re way off track and now need to listen to them—that's happening, and that's where my work has taken me. But, still, the erasure continues. The government is not giving back their lands still—we have things like Standing Rock and more recent iterations of that on a smaller scale happening in other places. Still, these gross injustices continue.

And so, I think Iraq helped get me in a place of knowing when to choose your battles and figuring out how to do work that needs to be done, but without the sacrifice of your soul in doing it, because for many years, that's what I did.

I'm very proud of my reporting from Iraq and of my first book. I'm glad I did it. But it was at great personal cost, for sure.

FARNSWORTH

Yes, I can imagine. There was something that came up when you were talking about all that, and it's going to sound a bit wonky. There was a visionary experience I had once, and it involves exactly something you were describing, and I want to share it.

The sort of visionary experience I had involved a small village, a very tightly-knit community of people who all loved and took care of each other, and were close with the land. Then, something starts to invade the surrounding land—it's not really defined or a specific thing. It's a darkness of sorts, one of violence. So, the warriors in this small community have to go out and fight this thing and prevent it from invading the community more. But as they go out, the thing poisons them, and affects them in a very particular way. They do incredible things to protect their community from the violence, but they bring some of that violence home inside themselves and start hurting people close to them: their partners and children, animals, and things like this. And so, the healers in the community have to figure out new techniques, rituals, ceremonies, and medicines to deal with this new thing. They don't understand it fully, but they have to practice something to learn how to heal those that are willing to put their bodies, minds, and souls on the line to protect everybody so that they don't bring that back in with them.

And I thought, when I had this experience and I came out of it, that this applies to any kind of work that people are doing. It doesn't literally mean you have to go out and fight a war, it just means you are partaking in protecting what is good, what is true, and what you love.

When you go out and do that, and participate in journalism, for instance—exposing war crimes on the ground—you are sacrificing an enormous part of who you are, to fight for truth. And when you come back, you are wrecked, and if you don't have those elders that you mentioned, to bring you into a circle and to understand you and your experience, not to necessarily "fix" you, but to help you move on a path to some sort of acceptance through the rage, destruction, and dysfunction that hurts those around you, then you're going to walk away and die on some level and become a ghost of sorts.

JAMAIL

There has to be a level of healing, you're exactly right. And again, there has to be a fundamental change that's a result of the healing.

As you and I talked about as friends, last June I was in a mountaineering accident where one of my best friends, actually my main climbing partner for 25 years, Troy Larson from Anchorage, was killed by rock fall. A rock hit him right below his helmet, right on his forehead. It was instant death, and we were roped up. It was an extremely traumatizing and challenging situation, to put it very diplomatically.

I got home eventually after dealing with the situation, and then started immediately talking to one of those aforementioned Indigenous elders—I ended up talking to both of them going through it. They both said, "Look, this is like Iraq. This is trauma, and it's always going to be with you. You're never going to get those visions out of your mind—you can't unsee what you saw and what you described to us around what happened. But, this is a pivot point in your life where you get to look at your life. You need to make some fundamental changes and get really clear about what your responsibilities are."

It was a pivot point, and started six months of extremely intense grieving and a really hard soul-searching. But at the end of that, some fundamental tectonic shifts were made in my life, one of which was made clear: I'm through doing that kind of climbing. It wouldn't be fair to my partner, her daughter, and other people that love and care about me, and it would be an abject neglecting of my other responsibilities in my life to other people.

I just bring that out as an example because, similar to Iraq, to have such a deep soul impacting experience, hard as it is, if that doesn't bring about some kind of internal change, along with the healing, then a huge part of the healing will be missed. At least that's been my experience from both of those.

Iraq changed my life. It changed how I see this country and my understanding of how power and Empire work. It changed how I viewed the dominant culture, and what the education system is in this country, etc. I don't want to get lost in the weeds, but I had to really try to understand how this is possible, and then make changes in my life accordingly.

And like I said, I live in a house in the woods in a pretty remote area for a reason, and can selectively choose if and when I'm going to go be around a bunch of people. I'm very fortunate to be able to do that, and it is by design. But more importantly, internally, I have to get really clear about what I can and can't do.

I have one more story. When I was on the eve of going to Iraq, I had an older friend of mine, who had similarly gotten to a point in her life a long time ago, where her conscience just kind of woke up. She'd been oblivious most of her life, and then she saw the world and all the imbalance and injustice: "Oh, my God, I got to do something." And she wrote Mother Teresa and asked, "What can I do to help?" She actually got a letter back, and it said, "Be kind to your neighbor." She told me that story, possibly, in part, to make me think twice about going to Iraq. Of course, it went in one ear and out the other. Some part of it obviously stuck, but I wasn't cognizant of that at the time.

So, I went to Iraq, and five books, hundreds and hundreds of articles, book tours, talks and lectures later, I'm no longer working as a journalist. I live in the woods, have a garden and chickens, and working on being kind to my neighbors. We sit around the fire together, and garden together sometimes. We've had to band together to deal with neighborhood issues involving guns. That's realistic work for me to do.

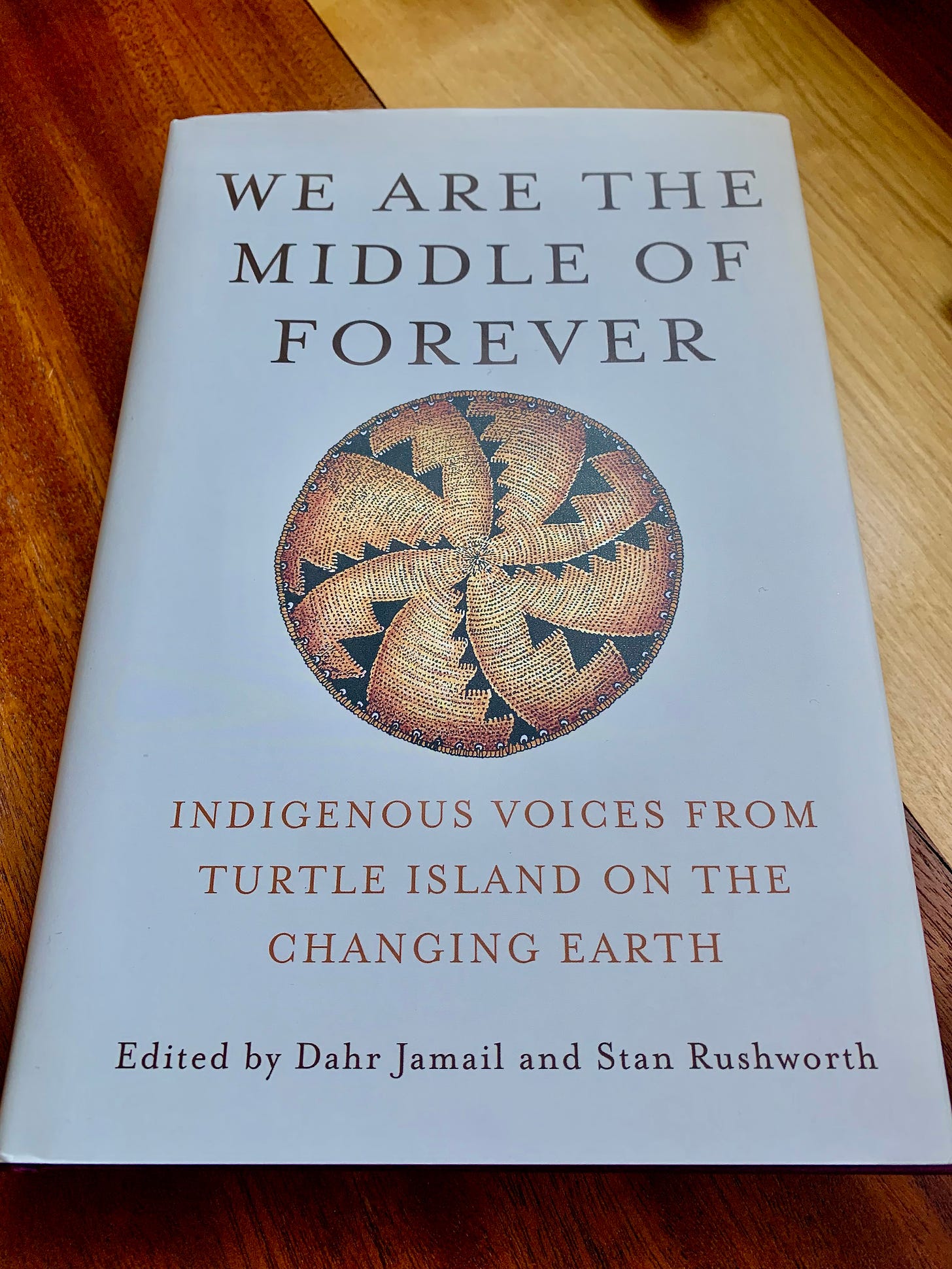

Moreover, I co-authored a book with a series of interviews with Indigenous people, to put that out and try to help bring a sense of calm and a deeper purpose to people who are struggling with what to do during these times. But the great irony to me—and it wasn't lost, thankfully—was that I had to live my way full circle all the way back around to what my friend told me 20-plus years ago, which is work on being kind to your neighbor, and then trust that other people, hopefully, are working to do the same thing.

I didn't stop the occupation of Iraq. I'm not going to stop the injustices being done to Indigenous people, or what I'm trying to bring to the light of day in my work. But, it's about figuring out what I can do today to help try to make things a little bit better. And so, it's come back around where it landed me, while I still, of course, keep my eyes on the bigger picture of things.

The core of that lesson is that I had to learn, and was taught by my elders, that it's more important how I comport myself. That has to come first, and not, "I'm going to just go do this thing that looks like a good thing to do to try to bring justice to a situation." I have to start with how am I going to comport myself. This is what I've learned from these Indigenous folks that we interviewed: it's just a reflection of the imbalance within us.

I've got to start working on balance within myself, before I have any prayer of going out and trying to bring balance and calm to anything outside myself.

FARNSWORTH

I have to say, when I do occasional checkups with you, and have seen what you've been doing on the land that you occupy, a certain kind of harmony and balance has been struck, but you still have to interact with your neighbors and the gun situation—I remember when you talked about that.

Being kind to your neighbors is probably the hardest thing we have to really do in this life. I think being kind to your neighbors includes even setting boundaries with them at certain points. There's a complex kind of relationship that comes with that, in actual practice.

Going to your space, you've developed something that is truly a place where love can flourish, and true relationship can exist. You've really honed in on that, especially since you've left journalism, but even before that, focusing on these things you just described. It's been beautiful for me to know you, and to see that happen over these years, and to get to know the various iterations of Dahr. It's been great as a friend, and as someone who's just intellectually curious as a podcaster and interviewer.

It's the kind of thing I have to balance because when I have these conversations with you, part of me wants to do an interview about this, but I have to respect that it's not always the time or place for it.

JAMAIL

Again, it's just been perfect timing.

I've had a couple of other interviews I did around the 20th anniversary of the Iraq invasion, one of them on Ralph Nader's program. Ralph Nader is a longtime hero of mine. It was with another person I also admire and respect, but, the interview was very heady and focused a lot on soldiers and money, and not so much on the Iraqi people. It was really hard to do.

It just makes a lot more sense to me, personally, to speak with you. This to me is like my 20-year Iraq anniversary interview—and it's not, it's a conversation. You're a friend, and I know that you approach your work in a very similar way that I tried to approach mine as a journalist, covering and investigating topics because it's what you really care about and what you feel is significant, and bringing that information out in a really heartfelt way. I think that's why people listen to your show regularly. They probably do so because they pick up on that, that there's got to be heart involved.

One of the Indigenous elders that my friend, Stan Rushworth, and I interviewed was Ilarion Merculieff, an Unangan, from the Aleutian Islands. He quotes the Yupik from Southwest Alaska, how the Yupik elders told him, “We live in this inside out society because we, in the Indigenous way, know that you live from your heart, that your heart tells your mind what to do. Your mind's only job is to implement what your heart is telling it to do.” And instead, dominant cultures flip that—it's all head.

I think it's probably an offshoot or a product of the change as a result of the healing work that's happened in my life, but with the heady stuff, I can't even hardly track it—I just start watching myself drift off. If something isn't coming from the heart, it just doesn't even feel real. So, why bother?

FARNSWORTH

I think that speaks to the nature of your approach and your work. What connects us on some level over the years, and why you felt comfortable coming on again, is because of the heart centeredness, I suppose.

But I just want to reflect on one thing, a final point on this story of discussing Iraq. It's the sense of why you chose the more difficult path. Describing you as an unembedded journalist is to say that you did not go into the embedded journalist program that the U.S. military had set up for journalists. They learned a certain lesson from the war in Vietnam, which is that any journalist could report on what's actually happening on the ground, and in a situation like that, it can change the consciousness of the public.

You were one of the few people reporting on the ground, and I remember this one situation where you had this interaction with what you called the "embeds"—these people who were part of the military convoy—and they said something to you that was so interesting, displaying such a disparity of realities. The embed, a photojournalist, said something about the bad guys: "Are the bad guys in there?" You were in some city that was about to be brutally assaulted by the U.S. military, and you had just gone through a checkpoint. You responded something like, "There are no bad guys.” They were thinking about this as a Manichean black and white, good versus evil issue: there are bad guys in there, and they're going to do bad things. That's not what's happening.

Speaking about the heart, you went in with the assumption that the truth would be among the people of Iraq. You spend some time in the book elaborating on the deep well of cultural history of this place, the beauty of their culture and the communities that exist there. They weren't just "Third World" peoples to cast off as casualties in a very "well-intentioned" war effort. You gave those people a voice.

You describe something that made it so heartbreaking to see exactly how this all played out for them, and that is a heart-centered practice. You demonstrated that 20 years ago, and that's what stuck out to me in this book.

JAMAIL

Thank you, Patrick.

That's what motivated me: a deep compassion for the Iraqi people, of knowing what they had been through from the first Gulf War to the genocidal sanctions, to everything that went on in that era, all at the hands of the U.S. government. When the war was launched, something in me snapped, and I think ultimately, at the core of it was I just wanted to go be with these people and do whatever I could. That part of it was genuine and from the heart. It came out in my reporting the best that I could. That's why I'm proud of that book: it's a log of that time.

There are thousands of pages—the first draft of that book was pushing 700–800 pages, and that was cut down from something bigger than that. It's because I cared and wanted to write about every aspect of it, so I covered it the best I could.

I'm glad that I went, and it's one of those things that now, 20 years on, I can say that regarding the Iraq war, I did what I could. I find great solace and being able to say that I didn't sit on the sidelines and wring my hands. I figured out something I could do and went and did it.

FARNSWORTH

Let me ask a final question here.

Now that we have come full circle, I think it's worth asking that since you formally left journalism behind as a career, you published a great book with Stan Rushworth, We Are the Middle of Forever, interviewing Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island.

You're still working in that field of documenting Indigenous perspectives. You are now involved in what has been described as a podcast miniseries through Post Carbon Institute, called Indigenous Voices on the Great Unraveling. I know it's your first foray into hosting a podcast series, so there is that element to it. It’s fascinating to see you come into this realm where I'm at.

Could you talk about what this project is, and give an idea of what to look out for in the coming months, or whenever it will be released?

JAMAIL

I'm very lucky to have the opportunity to host what's going to be an 8 to 12 part series where I'm going to be interviewing Indigenous people from around the world. The goal is to have someone from every continent, and then enough slots for extra folks to fill in for different reasons. I'm working with a producer, and it's something of an offshoot of the book I did with Stan, where we're just going to just interview folks who have been through these crises.

Indigenous people have survived—talking specifically about this country—genocide and ongoing erasure. They've survived so many things over history, and they're still here. And so, the core of the idea of the book I did with Stan came from, you want to talk about how to get through or at least comport ourselves during abrupt climate disruption? Take the Apache people from Arizona, put them on a train to south Florida, and then tell them that's where they got to live—there's your abrupt climate disruption. And they're still here. So, perhaps we should listen to what these folks have to say, not just about how to get through collapse, but how to comport ourselves during collapse—whether we get through it or not is out of our hands, ultimately.

What I'm trying to do with this podcast is just listen and put out a lot of wisdom and experience from people who've been here. Their ancestors have been living here for hundreds of years—here being living in a polycrisis.

The feedback Stan and I got from the book is that everyone who's read it has been genuinely grateful for it because they felt like it brought a sense of calm in a broader perspective. It doesn't give false hope, or anything like this. We had people in the book say—and I wouldn't be surprised if some of this comes out in the podcast—we have all these Indigenous stories, and not all of them end well. They're there to teach us a lesson that if you're doing something wrong, and you keep doing it and don't change, it's not going to end well.

So, that's in there too, along with a lot of really valuable tools and wisdom around how are we going to choose to comport ourselves, and wisdom earned the hard way. Working on the book, and I suspect working on this podcast, will be similar. It changed my perspective on all of this.

There's no question we're in collapse. There's no question we're on a planet that's being killed. There's no question that things are going to get worse. But it comes down to how are we going to choose to comport ourselves. How am I going to get up and find ways to serve the planet and future generations, or not? It comes down to that, and again, not being fixed on results. What kind of person am I going to choose to be during this time?

That's, I think, going to be the core theme of this podcast. We're going to get all the interviews done, and we hope to have it publicly available by September. It will be hosted on resilience.org, which is the website for Post Carbon Institute.

FARNSWORTH

I'm very much looking forward to seeing how this turns out. It's very fascinating to see over these years where your attention has been directed. While certainly leaving journalism behind was a transition, you're still doing basically the same thing, it's just now moving in different creative directions. It's been beautiful and heartening to see that you're still doing it, but in a very particular and creative way.

It gives me a sense of perspective if someday—and I've thought about this many times—I leave this podcast behind because it's too much and I’m too tired, that there's always other avenues to explore these subjects.

JAMAIL

Patrick, it just dawned on me listening to you now that the book with Stan and this podcast have become this synthesis of a sort of journalistic work while also healing at the same time, as opposed to a journalism where I keep taking in trauma. It's a form of journalism, but with a very different flavor, where for me to produce it, as well as for the reader and listener, it's going to bring a sense of calm and healing wisdom, as opposed to more difficult information to take in. I'm very fortunate for that.

I would say that many times that's what your podcast does, as well, and that's why I really appreciate it. So, thanks for your ongoing work. And I know you've had your struggles with burnout and such, as we've discussed, but I'm glad you're doing what you're doing. And I think that people appreciate it. I certainly appreciate it.

So, I appreciate you taking the time and having me on again.

Dahr Jamail is an award-winning author and journalist who formerly reported on climate disruption and environmental issues for Truthout. He is the author of multiple books, including The End Of Ice: Bearing Witness and Finding Meaning in the Path of Climate Disruption published in 2019, and most recently, We Are the Middle of Forever: Indigenous Voices from Turtle Island on the Changing Earth, co-written and co-edited with Stan Rushworth and released April 2022 by The New Press. Dahr is also the host of the upcoming podcast miniseries Indigenous Voices on the Great Unraveling produced by the Post Carbon Institute, which brings “forward the perspectives of Indigenous communities from around the world as humans and the more-than-human reckon with the consequences of global, industrial society built on growth, extraction, and colonialism.”